A “thumping heart” of solidified nitrogen controls Pluto’s breezes and may offer ascent to highlights on its surface, as per another examination.

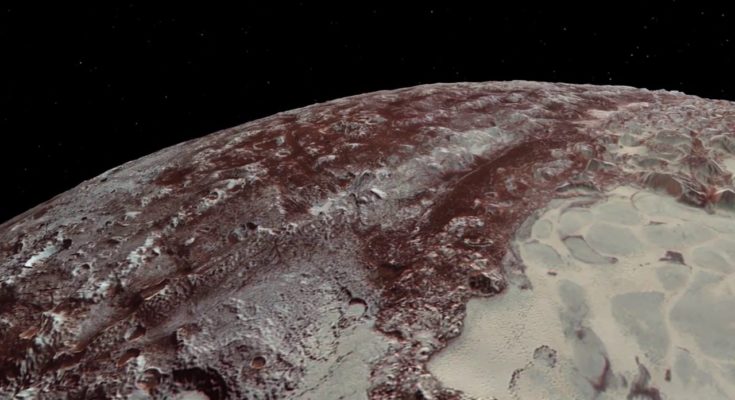

Pluto’s popular heart-formed structure, named Tombaugh Regio, immediately got well known after NASA’s New Horizons strategic film of the diminutive person planet in 2015 and uncovered it isn’t the desolate world researchers thought it was.

Presently, new research shows Pluto’s famous nitrogen heart leads its barometrical flow. Revealing how Pluto’s environment acts furnishes researchers with somewhere else to contrast with our own planet. Such discoveries can pinpoint both comparable and unmistakable highlights among Earth and a diminutive person planet billions of miles away.

Nitrogen gas — a component likewise found in air on Earth — contains the vast majority of Pluto’s slender climate, alongside limited quantities of carbon monoxide and the ozone harming substance methane. Solidified nitrogen additionally covers some portion of Pluto’s surface looking like a heart. During the day, a slender layer of this nitrogen ice warms and transforms into fume. Around evening time, the fume gathers and by and by structures ice. Each succession resembles a heartbeat, siphoning nitrogen twists around the smaller person planet.

New research in AGU’s Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets proposes this cycle pushes Pluto’s environment to course the other way of its turn — an extraordinary wonder called retro-pivot. As air whips near the surface, it transports heat, grains of ice and fog particles to make dim breeze streaks and fields over the north and northwestern locales.

“This features the way that Pluto’s climate and winds — regardless of whether the thickness of the air is exceptionally low — can affect the surface,” said Tanguy Bertrand, an astrophysicist and planetary researcher at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California and the examination’s lead creator.

The majority of Pluto’s nitrogen ice is limited to Tombaugh Regio. Its left “projection” is a 1,000-kilometer (620-mile) ice sheet situated in a 3-kilometer (1.9-mile) profound bowl named Sputnik Planitia — a region that holds the greater part of the smaller person planet’s nitrogen ice in light of its low height. The heart’s correct “flap” is involved good countries and nitrogen-rich icy masses that stretch out into the bowl.

“Prior to New Horizons, everybody thought Pluto would have been a netball — totally level, practically no assorted variety,” Bertrand said. “Yet, it’s totally unique. It has a variety of scenes and we are attempting to comprehend what’s happening there.”

Western breezes

Bertrand and their partners set out to decide how coursing air — which is multiple times more slender than that of Earth’s — may shape includes superficially. The group pulled information from New Horizons’ 2015 flyby to portray Pluto’s geology and its covers of nitrogen ice. They at that point mimicked the nitrogen cycle with a climate conjecture model and surveyed how winds blew over the surface.

The gathering found Pluto’s breezes over 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) hit toward the west — the other way from the smaller person planet’s eastern turn — in a retro-revolution during a large portion of its year. As nitrogen inside Tombaugh Regio disintegrates in the north and becomes ice in the south, its development triggers westbound breezes, as per the new investigation. No other spot in the nearby planetary group has such a climate, with the exception of maybe Neptune’s moon Triton.

The scientists additionally found a solid current of quick moving, close surface air along the western limit of the Sputnik Planitia bowl. The wind current resembles wind designs on Earth, for example, the Kuroshio along the eastern edge of Asia. Climatic nitrogen gathering into ice drives this breeze design, as per the new discoveries. Sputnik Planitia’s high bluffs trap the virus air inside the bowl, where it courses and gets more grounded as it goes through the western locale.

The serious western limit current’s presence energized Candice Hansen-Koharcheck, a planetary researcher with the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona who wasn’t associated with the new investigation.

“It’s particularly the sort of thing that is because of the geography or points of interest of the setting,” they said. “I’m intrigued that Pluto’s models have progressed to the point that you can discuss provincial climate.”

On the more extensive scale, Hansen-Koharcheck thought the new investigation was fascinating. “This entire idea of Pluto’s thumping heart is a magnificent perspective about it,” they included.

These breeze designs coming from Pluto’s nitrogen heart may clarify why it has dull fields and wind streaks toward the west of Sputnik Planitia. Winds could move heat–which would warm the surface–or could dissolve and obscure the ice by moving and saving dimness particles. In the event that breezes on the midget planet twirled an alternate way, its scenes may look totally changed.

“Sputnik Planitia might be as significant for Pluto’s atmosphere as the sea is for Earth’s atmosphere,” Bertrand said. “On the off chance that you evacuate Sputnik Planitia — in the event that you expel the core of Pluto — you won’t have a similar course,” they included.

The new discoveries permit analysts to investigate an extraordinary world’s climate and contrast what they find and what they think about Earth. The new examination additionally sparkles light on an article 6 billion kilometers (3.7 billion miles) away from the sun, with a heart that dazzled crowds the world over.

“Pluto has some riddle for everyone,” Bertrand said.

Disclaimer: The views, suggestions, and opinions expressed here are the sole responsibility of the experts. No Just Examiner journalist was involved in the writing and production of this article.